O tarihte ne olduğunu bilen ya da hatırlayanlar parmak kaldırsın.

Saturday, November 30, 2019

Bu da çok önemli bir makale.

Hani hep diyorum ya

Tasarruflar = Yatırımlar

doğru değildir diye. Çünkü doğrusu şu:

Tasarruflar = Yatırımlar + Net-Servet-Değişimi

O dönem içindeki net servet değişimi yokmuş gibi düşünülüyor. Halbuki var ve o tümüyle bir şeylerin sahipliğinden toplanan kira. Yani riba. Haramdır.

Bu makale onunla ilgili. Bu çalışmayı Michael, Dirk ve ben beraber yapacaktık da para bulamadığımızdan ben gidemedim.

Asset-price Inflation and Rent Seeking

Tasarruflar = Yatırımlar

doğru değildir diye. Çünkü doğrusu şu:

Tasarruflar = Yatırımlar + Net-Servet-Değişimi

O dönem içindeki net servet değişimi yokmuş gibi düşünülüyor. Halbuki var ve o tümüyle bir şeylerin sahipliğinden toplanan kira. Yani riba. Haramdır.

Bu makale onunla ilgili. Bu çalışmayı Michael, Dirk ve ben beraber yapacaktık da para bulamadığımızdan ben gidemedim.

Asset-price Inflation and Rent Seeking

Friday, November 29, 2019

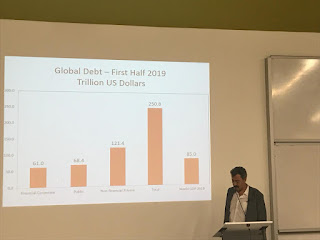

İki Olağanüstü Hal: İklim Değişimi ve Küresel Borç Yükü

İnsanlık bu iki sorunu çözemezse, ki bu iki sorun bağlantılı, oyulacak. Biri çözülemeden öbürü çözülemez. İklim değişimini engellemek için bu borç yükünü ortadan kaldırmak gerek. O borç yükünü ortadan kaldırmadan iklim krizini engellemek için gerekli yatırımlar ve yenilikler (inovasyon değil, o ticari çünkü) zamanında yapılamayacaklar. Para gerek bu işler için çünkü. Para ile borç arasındaki ilişkiyi göremeyenler ne dediğimi anlayamazlar ama olsun.

İnanılmaz. Gunder hakkında 2005'de yazdığım, dolar hakkında yazdığım iki yazının arasına girip ikinci olmuş.

Demek ki hala insalıktan ümit var. Hala dolar onlar için daha önemli ama Gunder için yazdığım iki dolar yazısının arasına girip ikinci olmuş ve üçüncü sıradaki ikinci dolar yazısını geçmiş. Neden acaba?

Gunder yazım

Çok özlüyorum Gunder'i.

O gittiği yerde hala haksızlıklarla savaşıyordur büyük olasılık, varsa öyle bir şans.

Allah rahmet eylesin.

Gunder yazım

Çok özlüyorum Gunder'i.

O gittiği yerde hala haksızlıklarla savaşıyordur büyük olasılık, varsa öyle bir şans.

Allah rahmet eylesin.

Climate Leviathan kitabından - İngilizce

"At times, taking the risk of being very wrong is more productive, and more modest, than maintaining a hesitant silence. We need to work on political visions of a world in which the movement has won—ideas of futures that can guide us in dark times, mobilizations to realize the change—even if those who propose them run the risk of seeming arrogant, of knowing more than can be known." — Wainwright and Mann, Climate Leviathan, 2018

Ne yapayım? Kitap İngilizce. Eskiden olsa Akatça olacaktı. Eskilerin ortak dili de Akatçaydı bir zamanlar. Neyse günün ortak dili, onu öğrenmek gerek.

Biraz da Almanca okumayı öğrendim ama o dili biliyorum dersem çok ayıp olur. Arapça ve Farsçayı daha çok biliyorum, mecburen yani. Şeş, beş, dübeş filan, o kadar Farsça biliyoruz.

Biraz da Almanca okumayı öğrendim ama o dili biliyorum dersem çok ayıp olur. Arapça ve Farsçayı daha çok biliyorum, mecburen yani. Şeş, beş, dübeş filan, o kadar Farsça biliyoruz.

Muhteşem bir kitap: Climate Leviathan

Climate Leviathan

A Political Theory of Our Planetary Future

Joel Wainwright and Geoff Mann

İngilizce biliyorsanız, okumanızı tavsiye ederim. Çok yeni bir kitap. 2018 basımı. Ben başladım, elimden bırakamıyorum. Libgen'den bedava indirilebiliyor. Bu yaşımıza geldik, hala okumayı bitiremedik. Olsun. Zararı yok, yararı var.

A Political Theory of Our Planetary Future

Joel Wainwright and Geoff Mann

İngilizce biliyorsanız, okumanızı tavsiye ederim. Çok yeni bir kitap. 2018 basımı. Ben başladım, elimden bırakamıyorum. Libgen'den bedava indirilebiliyor. Bu yaşımıza geldik, hala okumayı bitiremedik. Olsun. Zararı yok, yararı var.

Wednesday, November 27, 2019

Dirk Bezemer bizim makale hakkında şöyle dedi

This is a great historical, conceptual and practical text on private-debt restructuring. With this on the table it will be more difficult to brush off the idea as fanciful.

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

Zeynep beni ele verdi, Allah'a ısmarladı

Ben yokken evde Zeynep gitmiş.

Halbuki Ebu ve Hatçe hiç gitmediler. Ebu da Hatçe de Zeynep gibi sokak kedileriydi ve hep sokak kedisi olarak kaldılar ama hiç gitmediler. Zaman zaman içeride, zaman zaman dışarıda, ama hep buradaydılar.

Gerçi Ebu Hatçe'yi kovaladığından Hatçe biraz uzak kaldı mecburen ama olsun.

Zeynep kendi gitti.

Neden acaba?

Kimbilir?

Belki birgün gelir geri!

Belki de gelmez!

Halbuki Ebu ve Hatçe hiç gitmediler. Ebu da Hatçe de Zeynep gibi sokak kedileriydi ve hep sokak kedisi olarak kaldılar ama hiç gitmediler. Zaman zaman içeride, zaman zaman dışarıda, ama hep buradaydılar.

Gerçi Ebu Hatçe'yi kovaladığından Hatçe biraz uzak kaldı mecburen ama olsun.

Zeynep kendi gitti.

Neden acaba?

Kimbilir?

Belki birgün gelir geri!

Belki de gelmez!

Benim kısa bio - İngilizce

T. Sabri Öncü holds a BS and an MS in Mechanical Engineering and a

BS in Mathematics from Boğaziçi University, an MS and a PhD in Applied

Mathematics from the University of Alberta, and an MA in Business Research from

Stanford University. In addition to his years of experience as a practitioner

at several institutional money managers in the US, he had also served as the

Head of Research at the Centre for Advanced Financial Research and Learning, Reserve

Bank of India, Mumbai and as a Senior Economic Affairs Officer at the United

Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Geneva. He has many scientific

publications in respected international journals and books, and is a columnist

of the H. T. Parekh Finance Column of the

Economic and Political Weekly.

Neden İngilizce derseniz, mecburen.

Hıyarın biri de beni Stanford'tan MA in Business Research diplomam var dedim diye yalancılıkla suçlamıştı, oradan öyle bir diploma verilmiyor diye. Ulan, o diploma orada başlanmış ve bitirilmemiş ve fakat tüm doktora öncesi ders ve çalışmaları başarıyla bitirmiş doktora öğrencilerine verilen bir diploma. Bir tür teselli armağanı.

Hani benim altıncı bir diplomaya ne ihtiyacım vardı, o sorgulanabilir de, bu konuda yalan söylediğim iddia edilemez.

Hıyarın biri de beni Stanford'tan MA in Business Research diplomam var dedim diye yalancılıkla suçlamıştı, oradan öyle bir diploma verilmiyor diye. Ulan, o diploma orada başlanmış ve bitirilmemiş ve fakat tüm doktora öncesi ders ve çalışmaları başarıyla bitirmiş doktora öğrencilerine verilen bir diploma. Bir tür teselli armağanı.

Hani benim altıncı bir diplomaya ne ihtiyacım vardı, o sorgulanabilir de, bu konuda yalan söylediğim iddia edilemez.

Monday, November 25, 2019

Sunday, November 24, 2019

Thursday, November 21, 2019

Türkiye'de politik yolsuzluğun grafiği

Görüyor musunuz ne olduğunu?

AKP döneminde yolsuzluk Osmanlı dönemine çıkmış.

Yiyin efendiler yiyin, bu han-ı iştiha sizin,

Doyunca, tıksırınca, çatlayıncaya kadar yiyin!

Bu grafik şuradan: https://www.v-dem.net/en/analysis/CountryGraph/

AKP döneminde yolsuzluk Osmanlı dönemine çıkmış.

Yiyin efendiler yiyin, bu han-ı iştiha sizin,

Doyunca, tıksırınca, çatlayıncaya kadar yiyin!

Bu grafik şuradan: https://www.v-dem.net/en/analysis/CountryGraph/

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

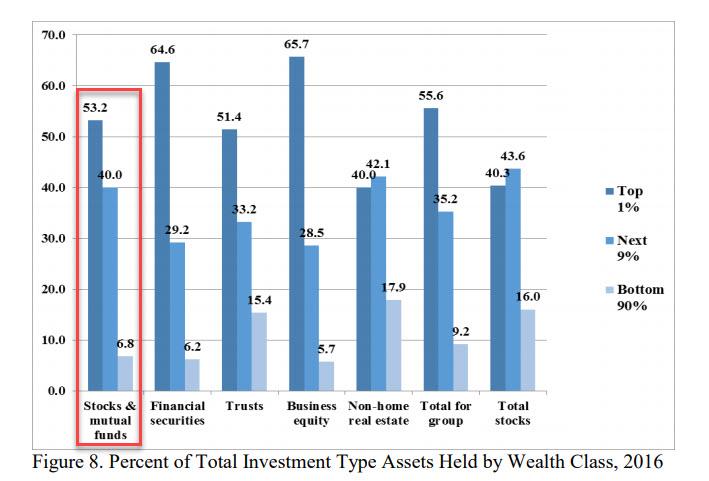

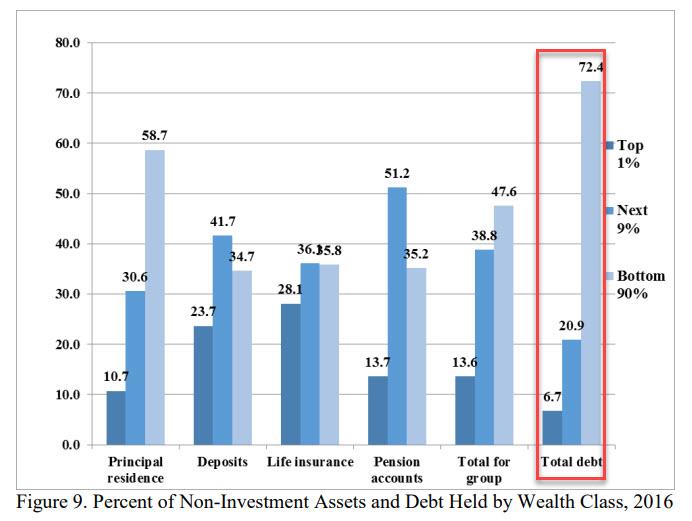

2018 Dünya Eşitsizlik Raporu - Türkçe

Rapor

Tavsiye ederim. Hazırlayan grubun başını çeken Piketty.

Siteleri burada:

https://wir2018.wid.world/

Bu da bu konuda ne yapılabilir üzerine bir makale, Zucman ve Saez'in yazdığı. Makale İngilizce.

Servet Vergisi

Tavsiye ederim. Hazırlayan grubun başını çeken Piketty.

Siteleri burada:

https://wir2018.wid.world/

Bu da bu konuda ne yapılabilir üzerine bir makale, Zucman ve Saez'in yazdığı. Makale İngilizce.

Servet Vergisi

Sunday, November 17, 2019

Papa Francis Katolik Kilisesinin günahlarına bir de "Ekolojik Günah" ekleyecekmiş.

Papayı destekliyorum. Bu günahı işleyenler cehennemde yakılsınlar cayır cayır. Sonsuza dek. Asla affedilmesinler.

Ekolojik Günah

Ekolojik Günah

Apple şimdi dünyanın en büyük şirketi - Nasıl oldu bu?

Çok basit. Kendi hisselerini geri satın alarak.

Halka açık hisseleri böyle azalıyor. Ve onlar böyle geri alındıkça, hisse fiyatları arttığından şirketin büyüklüğü de artıyor. Böyle giderse, Apple'ın 2030 yılında halka açık hiç hissesi kalmayacak. Bu geri alımlar için de düşük faizlerden borçlanıyor. Geçenlerde sıfır kuponlu tahvil satmış Avrupa'da.

Halka açık hisseleri böyle azalıyor. Ve onlar böyle geri alındıkça, hisse fiyatları arttığından şirketin büyüklüğü de artıyor. Böyle giderse, Apple'ın 2030 yılında halka açık hiç hissesi kalmayacak. Bu geri alımlar için de düşük faizlerden borçlanıyor. Geçenlerde sıfır kuponlu tahvil satmış Avrupa'da.

Önemli bir makale - Durumun en az 2007 kadar kötü olduğunun bir başka resmi

Hesaplaşma günü

İngilizce bir makale. Bu da bu makaleden bir grafik:

ABD hisse senedi piyasası büyüklüğünün, ABD yurtiçi gelirine oranı.

11 bin bilimcinin küresel iklim acil durumu deklarasyonu

Konuyla ilgili haber.

Bilimciler çok haklılar. 40 yıldır konu tartışılıyor ve dünya bu konuda 40 yıldır hiçbir şey yapmadı. Yakın zamanda da pek bir şeyler yapacak gibi durmuyor.

Bilimciler çok haklılar. 40 yıldır konu tartışılıyor ve dünya bu konuda 40 yıldır hiçbir şey yapmadı. Yakın zamanda da pek bir şeyler yapacak gibi durmuyor.

Su savaşları - Onlar da geliyor.

Zaten geldiler. İklim sorunu da derinleşiyor. Ama tabii Türkiye ekonomisi çok iyi. Çok çok iyi. Bu arada bizim sokakta çiçekler açmaya başladı, kafası karışan bitkiler bahar geldi sandıklarından herhalde. Bu tarihlerde İstanbul’da bahar havası olmaması gerek.

Su sorunu

Su sorunu

İran’da da halk sokağa çıkmış.

Bir sürü banka da yakmışlar. Halk ayaklanmaları yayılıyor. Bunlar böyle gidecek gibi duruyorlar. Çoğalarak.

İran benzin protestoları - 5 ölü

İran benzin protestoları - 5 ölü

Saturday, November 16, 2019

BIST100 - S&P500 Karşılaştırması.

Görüyor

musunuz ne olmuş? BIST100 ile S&P500 neredeyse birlikte hareket etmişler

2014 son çeyreğinden 2018 ilk çeyreğine dek, 2018 ilk çeyreğinden 2019 ortasına dek kopmuşlar. 2019 ortasından bu yana yine neredeyse birlikte hareket ediyorlar.

Bu ne demek? 2018 ikinci çeyreğiyle 2019 ikinci çeyreği arası bir sıkıntı olmuş

Türkiye'de. Sonra o sıkıntı geçmiş gibi duruyor. Şimdilik. Ben bu nedenle

çok ciddi bir uluslararası sorun çıkmazsa Türkiye dünyanın gerisinden çok

sapmaz diyorum. Dünya gittiğinde (ki gidecek) Türkiye de gidecek, tabii daha

önceden ciddi bir başka sorun çıkmazsa. Gördüğünüz gibi Türkiye ekonomisi,

finansı, bankaları kötü filan demiyorum. Bizimkiler çok iyi. Çok çok iyi de

dünya kötü. Çok kötü.

Friday, November 15, 2019

Bu da son EPW makalem. Finansal-olmayan Özel Borç Yükü - İngilizce

Non-financial Private Debt

Overhang

T. Sabri

Öncü

T. Sabri

Öncü (sabri.oncu@gmail.com) is an economist based in İstanbul, Turkey. This

article first appeared in the Indian journal, the Economic and Political Weekly

on 16 November, 2019.

Parts of this column are adopted from an article in

process that T. Sabri Öncü is co-authoring with Ahmet Öncü, titled " A

Partial Jubilee Proposal: Deleveraging Agencies Financed by Zero-Coupon

Perpetual Bonds."

Building on the International Monetary Fund

(IMF) Global Debt Database (GDD) comprising debts of the public and private

non-financial sectors for 190 countries

dating back to 1950, Mbaye et al (2018) identify a recurring pattern where

households and firms are forced to deleverage in the face of a debt overhang,

dampening growth, eliciting the injection of public money to kick-start the

economy.

They observe that this substitution of public

for private debt takes place whether or not the private debt deleveraging

concludes with a financial crisis, and deduce that this is not just a crisis

story but a more prevalent phenomenon that affects countries of various stages

of financial and economic development. They also find that whenever the non-financial

private sector is caught in a debt overhang and needs to deleverage,

governments come to the rescue through a countercyclical rise in government defi

cit and debt. If the non-financial private sector deleveraging concludes with a

financial crisis, "this other form of bailout, not the bank rescue packages,

should bear most of the blame for the increasing debt levels in advanced

economies."

Lastly, Mbaye et al (2018) note that their

results suggest that private debt deleveraging happens before one can see it in

the non-financial private debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio.

Global Debt Overhang

Recent data released by the International

Institute of Finance (IIF) indicate that debt overhang of the non-financial

private sector is worse in 2019 than it was in 2007. According to the IIF,

after reaching an all-time peak of about $248 trillion in the first quarter of

2018, despite contraction in the rest of 2018, and encouraged by falling

interest rates, global debt rose by $3 trillion in the first quarter of 2019,

reaching to about $246 trillion. Of this $246 trillion, while about $60

trillion is financial debt and about $67 trillion is government debt, about $73

trillion is non-financial corporate debt and about $47 trillion is household

debt. Thus, at a total of about $120 trillion, the non-financial private sector

dwarfs others in terms of its over-indebtedness.

Furthermore, these numbers are based mainly on

bank loans and debt securities. The IMF GDD all instruments data available for

45 of the 190 countries imply that these numbers grossly underestimate the

actual non-financial private debt. Given that the world GDP was about $85

trillion in 2018, the global non-financial private sector debt to GDP ratio

must be way above 150%. In light of history, a global non-financial private

debt deleveraging is therefore inevitable, and the coming round may be worse

than the previous round that started in 2007.

Orderly or Disorderly?

At this level of global non-financial debt

overhang, the non-financial private sector will deleverage, and in the absence

of other mechanisms, the two “bailouts” that Mbaye et al (2018) mentioned will

come.

As the former chief economist of the Bank for

International Settlements (BIS) William R White said in an interview in 2016

(Evans-Pritchard 2016):

"The situation is worse than it was in 2007. Our macroeconomic

ammunition to fight downturns is essentially all used up ... It will become

obvious in the next recession that many of these debts will never be serviced

or repaid, and this will be uncomfortable for a lot of people who think they

own assets that are worth something ... The only question is whether we are

able to look reality in the eye and face what is coming in an orderly fashion,

or whether it will be disorderly."

It is with this question in mind that I now

turn to the German Currency Reform of 1948. A few years after the end of World

War II, three of the Allied powers occupying the western zones of Germany, the

United States (US), the United Kingdom, and France had started a currency

reform in their zones in 1948.

German Currency Reform

of 1948

At the insistence of the US, they set up a

decentralised central banking system consisting of independent state (land)

central banks in the 11 states in their zone, and a joint subsidiary of the

Land Central Banks, the Bank deutscher Länder (BdL), much like the Federal

Reserve System in the US.

The original plan consisted of: (i) conversion

of currency and debts at a ratio of 10 Reichsmarks (RMs) for one Deutschemark

(DM); and (ii) a fund built with a capital levy for the equalisation of burdens

(Lastenausgleich), which would correct part of the inequity between owners of

debt, and owners of real assets and shares of corporations (Kindleberger 1984).

The DMs printed in the US were flown, and the

reform began on 20 July 1948. To avoid moral hazard problems, the conversion

laws from RM to DM were announced to be published a week later, on 27 July

1948. However, hardly does any project get implemented as planned. The

announced conversion laws included provisions to cancel all accounts and

securities issued by the Reich so that barring a future radical

Lastenausgleich, the reform imposed the burden of war almost entirely on

holders of paper claims against the Reich (Hughes 1998).

The first step in the currency change provided

only for the surrender of the old RMs, which were thereafter valueless, merely

enough new money for each individual and fi rm to meet their essential needs

for about two weeks (Bennet 1950). Each individual received 60 DM in two

instalments (40 DM–20 DM). Firms and tradesmen received 60 DM per employee. The

recurring RM payments, including wages, rents, taxes, and social insurance

benefits, as well as prices other than those of debt securities, were fixed at

a conversion rate of 1:1. While the remaining debts were written down to

100:10, in the course of a few months, currency and deposits had been written

down to 100:6.5, effectively.

The result was that about 93.5% of the pre-1948

savings of West Germans in their accounts were abolished. Since the less

affluent had kept their savings in savings accounts mostly while the more

affluent in mortgages and bonds, the less affluent paid more for the war

burdens than the more affluent. Furthermore, real property holders fortunate

enough to avoid war damages had escaped unscathed as the tax system spared

profits to encourage self-financing, and corporations preserved about 96% of their real assets (Hughes 1998).

Although the notion can be traced back to 1943,

the Lastenausgleich Law was passed after the establishment of the Federal

Republic of Germany on 23 May 1949. Enacted on 18 July 1952, and effective from

1 September 1952, it increased compensation of the savers by an additional

13.5% so that their loss was reduced to 80% (Hughes 2014). The law also imposed

a nominal 50% capital levy on capital gains, but allowed payment in instalments

over 30 years, making the levies merely an additional property tax (Hughes

1998).

Equalisation Claims

There is no doubt that the 1948 currency reform

distributed the war burdens among West Germans unfairly, favouring the

propertied over the property-less. However, it made the non-financial private

sector consisting of households and firms of West Germany start from an almost

clean slate. Further, the London Debt Agreement of 1953 erased about 51% of its

foreign debt, and the remaining debt was linked to its economic growth and

exports such that the debt service to export revenue ratio could not exceed 3%.

Then came the economic miracle of West Germany. West Germany had moved from

being a large net debtor at the end of the war to a creditor by the middle of

the 1950s (Buchheim 1988), although other factors too had played a role

(Eichengreen and Ritschl 2009). What caused the economic miracle of West Germany has been a topic for

hot debate. While some argue for the foreign debt relief of 1953, others argue

for the currency reform of 1948, and some others argue for other reasons, the

debates continue.

The original reform plan was to convert currency

and all debts at a ratio of 10: 1, leaving everything else intact. Had that

happened, the balance sheets of all financial institutions would have remained unimpaired,

assuming no bad loans. However, the conversion laws of the actualised reform

were such that they required all financial institutions to remove from their

balance sheets any securities of the Reich and cancel all accounts and currency

holdings of the Reich, the Wehrmacht, the Nazi Party and its formations and

affiliates, and certain designated public bodies. This impaired balance sheets

of nearly all of the financial institutions.

The solution that the conversion laws offered

was the equalisation claims. One of the provisions of the laws contained the

following statement (Bennet 1950):

"Financial institutions to receive state equalisation claims to

restore their solvency and provide a small reserve if either or both were

impaired by these measures.

The equalisation claims were interest-bearing

government bonds of a then non-existing government and had no set amortisation

schedules. They were just placeholders on the assets side of the balance sheets

to ensure that the financial institutions looked solvent. They were just some

numbers created by the Office of Military Government for Germany, US (OMGUS),

headed by General Lucius Clay of the US Army. They later became bonds of the

Federal Republic of Germany, established on 23 May 1949.

The OMGUS created approximately 22.2 billion DM

of equalisation claims, of which 8.7 billion DM were allocated to the BdL, 7.3

billion DM to credit institutions, 5.9 billion DM to insurance companies and 66

million DM to real estate credit institutions. Interest rates on the claims

allocated to the BdL, the Land Central Banks, and private credit institutions

were generally 3%. Insurance companies and real-estate credit institutions

received 3.5% and 4.5% respectively (van Suntum and Ilgmann 2013). These claims

could only be traded among the financial institutions, and only at their face

values, making them non-marketable (Michaely 1968).

Later in 1955, an agreement between the BdL and

the government allowed the BdL to sell the equalisation claims at any price.

After that, the equalisation claims came to also be called as the “mobilisation

paper,” since the BdL “mobilised” them for open market operations. The

equalisation claims were used a second time in 1990, during the German

reunification, because unified Germany also faced a severe balance sheet

problem in the financial sector, again resulting from an unequal conversion of

assets and liabilities.

So, the equalisation claims are well tested,

and historians have found no evidence that the equalisation claims imposed any

long-term negative repercussions on either the viability of financial markets

or economic growth (van Suntum and Ilgmann 2013).

Can we design a globally coordinated debt

deleveraging mechanism using some version of equalisation claims, possibly in

the form of zero-coupon perpetual bonds with no cost to anyone, so that we are

able to look reality in the eye and face what is coming in an orderly fashion?

References

Bennet, J (1950): “The German Currency Reform,” The

Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol 267, pp

43–54.

Buchheim, C (1988): “Die Währungsreform 1948 in

Westdeutschland,” Vierteljahrsh Zeitgesch, Vol 36, pp 189–231.

Eichengreen, B and A Ritschl (2009): “Understanding West

German Economic Growth in the 1950s,” Cliometrica, Vol 3, pp

191–219.

Evans-Pritchard, A (2016): “World Faces Wave of Epic Debt

Defaults, Fears Central Bank Veteran,” Daily Telegraph, 19 January.

Hughes, M (1998): “Hard Heads, Soft Money? West German

Ambivalence about Currency Reform, 1944–48,” German Studies Review, Vol

21, No 2, pp 309–27.

— (2014): Shouldering the Burdens of Defeat:

West Germany and the Reconstruction of Social Justice, Chapel Hill and

London: The University of North Carolina Press.

Kindleberger, C P (1984): A Financial History of

Western Europe, London: George Allen & Unwin.

Mbaye, S, M Moreno-Badia and K Chae (2018): “Bailing Out

the People? When Private Debt Becomes Public,” IMF Working Paper 18/141.

Michaely, M (1968): “Germany,” Balance-of-Payments

Adjustment Policies: Japan, Germany, and the Netherlands, Michael Michaely

(ed), New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, pp 58–84.

van Suntum, I and C Ilgmann

(2013): “Bad Banks: A Proposal Based on German Financial History,” European

Journal of Law and Economics, Vol 35, pp 367–84.

İşte bunu biz de önereceğiz. Küresel servet vergisi

Abolish the billionaries?

Yani borç silmek yetmez. Yüklerin de paylaşılması gerek. Bu yüzden, kademeli bir servet vergisi gerekli.

Yani borç silmek yetmez. Yüklerin de paylaşılması gerek. Bu yüzden, kademeli bir servet vergisi gerekli.

Sürdürülebilir kapitalizm modası. Bu yeni bir moda.

Sürdürülebilir Piyasalar Girişimi

İngilizce yazı. Bir okuyun neler diyorlar. Onlar da olanın sürdürülmez olduğunun farkındalar. Ama hala piyasalar diyorlar. Ne demek sürdürülebilir piyasalar? Sistemik bir değişiklik, bir devrim gerek. Ama benim pek umudum yok. Yerine savaşlar gelecek. Gidişat o gibi duruyor.

İngilizce yazı. Bir okuyun neler diyorlar. Onlar da olanın sürdürülmez olduğunun farkındalar. Ama hala piyasalar diyorlar. Ne demek sürdürülebilir piyasalar? Sistemik bir değişiklik, bir devrim gerek. Ama benim pek umudum yok. Yerine savaşlar gelecek. Gidişat o gibi duruyor.

Biz buna küresel borç krizi diyoruz.

Borç krizi

Küresel borç yine rekor kırmış. Bu borçlar ödenemez. Önemli bir kısmının silinmesi gerek. Şu videoya bir daha bakın isterseniz.

Küresel borç yine rekor kırmış. Bu borçlar ödenemez. Önemli bir kısmının silinmesi gerek. Şu videoya bir daha bakın isterseniz.

Türkiye'de bütçe açığı büyüyor. Son derece normal.

Çünkü yalnızca Türkiye'de değil, dünyada hanehalkları ve finansal-olmayan şirketler, yani finansal-olmayan özel sektör kaldıraç düşürüyor. Kısmen gönüllü olarak, kısmen de yeni borç bulamadığından. Böyle olduğunda da hükümet borcu artıyor. Olanı bizim makaledeki özetle IMF'nin ağzından dinleyin:

Possibly also because World War II led to a

deep private debt deleveraging of households and non-financial firms, and

therefore non-financial private sectors of many countries started their journey

after the end of World War II at low debt levels, majority of the

first-tradition economists had concerned themselves mostly with public debt

without paying much attention to private debt, at least, from the end of World

War II until the onset of the GFC in the summer of 2007. The GFC that started

in the summer of 2007 changed that. Now there is a burgeoning literature also among

the first-tradition economists on the dangers of the excessive debt leverage of

the non-financial private sector as documented by Mbaye, Moreno-Badia and Chae

(2018, 2019). Mbaye, Moreno-Badia and Chae (2019) opened their article as

follows.

"The

Global Crisis, along with ravaging the world economy, has awoken economists to

the dangers of unchecked private debt. Excessive private leverage has been

linked in recent papers to increased risks of financial crises (Schularick and

Taylor 2012), weaker recoveries (Mian et al. 2013), and lower medium-term

growth (Mian et al. 2017)."

Comprehensive lists of papers by

first-tradition economists on the subject are given in Mbaye, Moreno-Badia and

Chae (2018) and Mbaye, Moreno-Badia and Chae (2019). It is evident from their

papers, the papers they cited and others that the first-tradition economists

have been unaware of the works of the second-tradition economists on the

subject.

Building on the IMF Global Debt Database

(GDD)—by far the richest dataset for the analysis of indebtedness when compared

to those of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD),

Bank of International Settlements (BIS), International Institute of Finance

(IIF), and McKinsey—comprising debts of the public and private non-financial

sectors for an unbalanced panel of 190 countries dating back to 1950, Mbaye,

Moreno-Badia and Chae (2018) document a recurring pattern where households and

firms are forced to deleverage in the face of a debt overhang, dampening

growth, and eliciting injection of public money to kick start the economy.

They observe that this substitution of public

for private debt takes place whether the private debt deleveraging concludes

with a financial crisis or not, and deduce that this is not just a crisis story

but a more prevalent phenomenon that affects countries of various stages of

financial and economic development. They also find that whenever the

non-financial private sector is caught in a debt overhang and needs to

deleverage, governments come to the rescue through a countercyclical rise in

government deficit and debt, and that if the non-financial private sector

deleveraging concludes with a financial crisis, "this other form of bailout,

not the bank rescue packages, should bear most of the blame for the increasing

debt levels in advanced economies."

Finally, Mbaye, Moreno-Badia and Chae (2018)

note that their results suggest that private debt deleveraging happens before

one can see it in the non-financial private debt to Gross Domestic Product

(GDP) ratio.

Possibly also because World War II led to a

deep private debt deleveraging of households and non-financial firms, and

therefore non-financial private sectors of many countries started their journey

after the end of World War II at low debt levels, majority of the

first-tradition economists had concerned themselves mostly with public debt

without paying much attention to private debt, at least, from the end of World

War II until the onset of the GFC in the summer of 2007. The GFC that started

in the summer of 2007 changed that. Now there is a burgeoning literature also among

the first-tradition economists on the dangers of the excessive debt leverage of

the non-financial private sector as documented by Mbaye, Moreno-Badia and Chae

(2018, 2019). Mbaye, Moreno-Badia and Chae (2019) opened their article as

follows.

"The

Global Crisis, along with ravaging the world economy, has awoken economists to

the dangers of unchecked private debt. Excessive private leverage has been

linked in recent papers to increased risks of financial crises (Schularick and

Taylor 2012), weaker recoveries (Mian et al. 2013), and lower medium-term

growth (Mian et al. 2017)."

Comprehensive lists of papers by

first-tradition economists on the subject are given in Mbaye, Moreno-Badia and

Chae (2018) and Mbaye, Moreno-Badia and Chae (2019). It is evident from their

papers, the papers they cited and others that the first-tradition economists

have been unaware of the works of the second-tradition economists on the

subject.

Building on the IMF Global Debt Database

(GDD)—by far the richest dataset for the analysis of indebtedness when compared

to those of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD),

Bank of International Settlements (BIS), International Institute of Finance

(IIF), and McKinsey—comprising debts of the public and private non-financial

sectors for an unbalanced panel of 190 countries dating back to 1950, Mbaye,

Moreno-Badia and Chae (2018) document a recurring pattern where households and

firms are forced to deleverage in the face of a debt overhang, dampening

growth, and eliciting injection of public money to kick start the economy.

They observe that this substitution of public

for private debt takes place whether the private debt deleveraging concludes

with a financial crisis or not, and deduce that this is not just a crisis story

but a more prevalent phenomenon that affects countries of various stages of

financial and economic development. They also find that whenever the

non-financial private sector is caught in a debt overhang and needs to

deleverage, governments come to the rescue through a countercyclical rise in

government deficit and debt, and that if the non-financial private sector

deleveraging concludes with a financial crisis, "this other form of bailout,

not the bank rescue packages, should bear most of the blame for the increasing

debt levels in advanced economies."

Finally, Mbaye, Moreno-Badia and Chae (2018)

note that their results suggest that private debt deleveraging happens before

one can see it in the non-financial private debt to Gross Domestic Product

(GDP) ratio.

Wednesday, November 13, 2019

Ekonomistler bu konuyu bir düşünsünler: Hazine tahvillerinin önemi

This is where the Treasury

comes in. The Treasury provides most of the collaterals acceptable to the

Central Bank through which the Central Bank creates most of the reserves.

Further, the Treasury maintains the account from which it makes its payments at

the Central Bank in all countries, although it may maintain accounts at some

designated commercial banks also (see Yaker and Pattanayak 2010). We should

mention that, leaving aside the questions of why and since when, the Central

Bank currently cannot directly lend to or directly purchase securities from the

Treasury in any country. The "central bank independence" reigns

supreme by law, although not necessarily in practice.

Other than banks and the

Treasury, there usually are a few other entities that are allowed to maintain deposit

accounts at the Central Bank in every country, not to mention foreign central

banks. All deposits other than bank deposits at the Central Bank, including

reverse repurchase liabilities, drain reserves if they go up. In other words, all

deposits other than bank deposits at the Central Bank should be viewed as a

fourth type of money, since changes in their balances impact reserves, that is,

base money, so that they should be managed in order not to create liquidity

problems in the domestic banking system (see, for example, Pozsar 2019).

We conclude this section

with the following observations.

1) When the Treasury sells

its bonds to the non-bank rest, there is no new money creation. Only existing

money changes hands, and if that money gets deposited in the TSA, equal amounts

of reserves and deposits get extinguished. Likewise when tax payments get

deposited in the TSA. But after the

Treasury spends the deposited amount, both base money and broad money come back to where they were

before, keeping everything else constant.

2) When the Treasury sells

its bonds to banks, three things may happen.

a) If there are banks at

which the Treasury can maintain deposit accounts with or without

restrictions, or there are no such banks and only those banks at which the

Treasury cannot maintain deposits accounts purchase the Treasury bonds, then

these banks buy the Treasury bonds by borrowing from the Central Bank against

which the Central Bank increases the balance of the TSA. After the Treasury

spends the balance, an equal amount of base and broad money get created.

b) If there are banks at

which the Treasury can maintain deposit accounts without restrictions and only

those banks at which the Treasury can maintain deposit accounts without

restrictions purchase the Treasury bonds, then new broad money gets created as

usual. But since the Treasury has to spend only from the TSA, the result is the

same as above.

c) If there are banks at

which the Treasury can maintain deposit accounts with restrictions and only these

banks purchase the Treasury bonds, then a combination of the above two happens.

These observations mean that whether the Treasury sells some bonds to banks or the same amount directly to the Central Bank (or the Central Bank loans the same amount to the Treasury), the changes in the base and broad money are the same after the Treasury spends the amount, keeping everything else constant. The latter is, of course, cheaper for the Treasury because the Central Bank has to pay a large percentage of its profits to the Treasury in every country, whereas the banks, generally, do not.

Tuesday, November 12, 2019

İsteyen olursa bana yazsın.

Çok güzel bir bebek. Biraz da hasta bir sokak kedisi. Benim eve geldi ama benim büyük kedi Ebu Süfyan bunu evde tutmaz. İsteyen olursa bana sabri.oncu@gmail.com adresimden yazsın, tanıştırabilirim. Ama herkese vermem yani kızımı. Allahın emri, peygamberin kavliyle isteyeceksiniz. Siz onu sevebilirsiniz ama onun da sizi sevmesi ön koşul.

Bunun adı Zeynep, bu arada. Bu işin uzmanı değilim ve bir sürü yanılanı gördüm kaç kez ama eğer erkekse de Hüseyin. Erkek olduğunu hiç sanmıyorum ama bir veterinere sormakta yarar olabilir. Yanılınabiliyor. Bir de bunu kısırlaştırmayacaksınız. Öyle yapacağım derseniz ya da öyle yapacağınızı hissedersem, vermem. Ne de olsa "moral hazard (ahlaki tehlike)" denilen şey nedir, biraz biliyorum.

Ben şimdi bunu nasıl Türkçeye çevireyim? Modern Para Üretimi - İngilizce

Bu kardeşim Profesör Öncü ile yazdığımız makalenin bir bölümü ve makalenin bu bölümünü ben yazdım mecburen, bu konu benim konu olduğundan. Henüz bitmedi ama az kaldı. İngilizce okuyabilenlerin işine yarar belki.

Sonradan ek: Bitti.

Modern Money

Creation

"It

is much more realistic to say that the banks 'create credit,' that is, that

they create deposits in their act of lending, than to say that they lend the

deposits that have been entrusted to them. And the reason for insisting on this

is that depositors should not be invested with the insignia of a role which

they do not play. The theory to which economists clung so tenaciously makes

them out to be savers when they neither save nor intend to do so; it attributes

to them an influence on the 'supply of credit' which they do not have. The theory of 'credit creation' not only recognizes

patent facts without obscuring them by artificial constructions; it also brings

out the peculiar mechanism of saving and investment ... Nevertheless, it proved

extraordinarily difficult for economists to recognize that bank loans and bank

investments do create deposits." − Joseph Alois Schumpeter (1954)

The above is from Schumpeter's History of Economic Analysis, published

in 1954. Let us now look at two earlier works: Henry Dunning Macleod's The Theory and Practice of Banking, published in 1855-6 in two

volumes, and Robert Harrison Howe's The

Evolution of Banking: A Study of the

Development of the Credit System, published in 1915. Both scholars go at

lengths to describe how modern banks create deposits by extending credit or

buying real and financial assets. Building on Macleod (1866 [1855-6]), one of

the most influential early proponents of the Credit Creation Theory (CCT) of banking, Howe (1915) defines modern banks as follows.

"Our

modern banks are Banks of Discount as distinguished from their predecessors,

the Banks of Deposit, and have given an enormous impetus to commerce. They have

been able to do this because they can and do create credit that circulates the

same as money and in a far more convenient, safe and economical form."

Ravn (2019) clarifies as follows.

"In

a nutshell, other financial, non-bank firms can lend alright, but they pay out.

Banks don’t. Credit that is entered into a firm’s Accounts Payable during

lending is, in a bank, never discharged, but is renamed Customer Deposits and

serve as the money supply, by virtue of this credit being transferable and

accepted in payment by other banks and their customers."

Although not accepted as a universal truth,

the CCT had remained the dominant theory of banking until the early 1930s when

the Fractional Reserve Theory (FRT), one of the early proponents of which was

Alfred Marshal (1888), had replaced the CCT as the dominant theory.

The FRT can be summarized as follows.

Some seed money comes to the banks, and the

banks multiply that seed money. The banks do this multiplication by keeping a

percentage of that money as reserves and

extending the rest as loans to the public, which ends up as deposits at some

other banks. The banks then keep doing this among themselves until there is no

money left to lend and, in the process, create additional deposits—that is,

additional money—whose sum is equal to the sum of the loans extended. For

example, if the reserve ratio the banks abide by is 10%, the banks multiply the

seed money by 10.

Therefore, the FRT can also be called the

Deposit Multiplication Theory (DMT) in which although each bank is a financial

intermediary, the banking system creates money collectively as described above.

Whether the DMT or the FRT, the theory had remained in the back burner until

the end of World War I, when it started to gain prominence. One of the most

influential proponents of the FRT was Phillips (1920), and there had been many

others. By the early 1930s, it became the dominant theory and had remained so

until the 1960s.

The theory that replaced the FRT as the

dominant theory is the Financial Intermediation Theory (FIT) of banking, one of

the early proponents of which was von Mises (1912). The FIT challenge to the

FRT started with the seminal paper of Gurley and Shaw (1955) in which they

argued against the view that “banks stand apart in their ability to create

loanable funds out of hand while other intermediaries in contrast are busy with

the modest brokerage function of transmitting loanable funds that are somehow

generated elsewhere.” Later, Gurley and Shaw (1960) argued that the

similarities between the monetary system and non-monetary intermediaries are

more important than the differences, and that, like other financial

intermediaries, banks and the banking system have to collect deposits and then

lend them out. Then came the support of Tobin (1963) after which the FIT became

the dominant theory and had remained so, at least, until the start of the GFC

in the summer of 2007.

While Werner (2014, 2016), and Jakab and

Kumhof (2015, 2019) give detailed historical accounts of the evolution of the

three banking theories, Werner (2014, 2016) also provides empirical tests

rejecting the FRT and FIT and showing that the CCT alone conforms to empirical

facts. An earlier empirical work rejecting the FRT is a Fed working paper in

which Carpenter and Demiralp (2010) demonstrate that the relationships implied

by the FRT do not exist in the data.

More recently, Ravn (2019) examined the three theories, and although he

did not dispute the validity of the CCT for the current banking and monetary

system, concluded that the FRT and FIT do not need to be condemned to the dust bin

of history because the money incarnations of each banking theory facilitate

their appropriate use in analysis of historical and future banking and monetary

systems and argued that although under current conditions individual banks can

and do indeed create money all on their own, one should not downplay the

enabling role that clearing plays in facilitating money creation, absorbing the

money created and concealing the origin of money in banks' credit creation.

A fourth theory which had remained at the

fringes until recently is the State Theory of Money—also known as chartalism (the

Latin word "charta" means ticket, token or paper)—formulated by George

F. Knapp (1973 [1905]). According to Knapp who coined the name chartalism, money

is "a creature of the state", and Rochon and Vernengo (2003) argue

that Knapp seems to suggest that this is because the State determines the unit

of account. Indeed, citing Knapp, Keynes (1930) also asserts that "the age

of chartalist or State money was reached when the State claimed the right to

declare what thing should answer as money to the current money of account—when

it claimed the right to enforce the dictionary but also to write the

dictionary", and that "[t]oday all civilized money is, beyond the

possibility of dispute, chartalist." Later, Abba Lerner (1947) brought to

the fore taxation as the main cause for the acceptability of money because

"before the tax collectors were strong enough to earn for the State the

title of creator of money, the best the State could do was tie its currency to

gold or silver," although neither Knapp nor Keynes made such a claim.

The Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) —also known

as neo-chartalism—recently popularized by the American politicians Bernard

Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio Cortez is a form of chartalism. Wray (2014)

describes the role chartalism plays in the MMT, and Lavoie (2014) provides a

friendly critique of neo-chartalism (also see Rochon and Vernengo 2003). According

to the MMT, money is injected into the system by the government as the monopoly

issuer of currency, and the banking sector leverages the government-injected

money, increasing the amount of money in circulation. While the MMT argues that

what is necessary for the existence of a monetary economy is the State power to

create money and to ensure its general acceptance by imposing taxes, many of

its critics object to the MMT emphasis on taxes and argue that what is

essential for the existence of a monetary economy is the State's ability to

enforce the civil law of contracts under which contracts are settled.

Although the origins of the MMT go back to

the early 1990s and debates on neo-chartalism have been going on for longer

than a decade, since many new supporters and opponents have jumped in the wagon

after the MMT became popular in the summer of 2018, the intensity of the

debates has been growing. The reader can consult, for example, the October 1,

2019 issue of the Real-world Economic Review for a recent debate.[1]

A detailed discussion of the MMT is

beyond the scope of this article. However, focusing only on the payment and

settlement aspects of the MMT, we mention that an important contribution of the

MMT is the clarification of the role the Treasury account at the Central Bank—the

Treasury General Account (TGA) in the US and the Treasury Single Account (TSA)

in most other countries (see, for example, Yaker and Pattanayak 2010)—plays in

the money creation process.

In the rest of this section, we give a brief

description of domestic money creation, which we will need in the next section.

In many jurisdictions, domestic banks can create foreign currency (mainly US

dollar and euro) deposits by extending foreign currency loans also, but we

leave this out for simplicity. Further, we avoid discussing the roles the

international monetary system, as well as shadow banks, play in modern money

creation also for the same reason.

Since we ignore the shadow banks and the rest

of the world for simplicity, there remain four major players in domestic money

creation: (1) the Treasury, (2) the Central Bank, (3) the banks, and (4) the non-bank

rest consisting of non-bank financial corporations, non-financial corporations,

and households. A fifth player is the banking regulator unless the Central Bank

is it, and there are many jurisdictions in which there are multiple banking

regulators. Irrespective of the case, however, it is always the Central Bank

that sets the reserve requirement as the reserve requirement is a monetary

policy tool, whereas the banking regulator sets the capital requirement (see,

for example, Öncü 2017 for a detailed discussion), among other things.

The three primary types of money in current domestic

monetary systems are (1) cash (banknotes and coins), (2) reserves (deposits of

the banks at the Central Bank), and (3) customer (non-bank rest) deposits at

the banks or, for short, deposits. Deposits are claims on the Treasury created

cash, as well as on the Central Bank created reserves. As empirically demonstrated by Werner (2014,

2016), only the CCT conforms to empirical facts, meaning banks create deposits

by extending loans and purchasing real or financial assets. Or, in Schumpeter's

words, "bank loans and bank investments do create deposits (Schumpeter

1954)."

However, as Carney (2013) pointed out, bank

"loans create a lot more than deposits," and we add that the same is

true also for bank investments, that is, bank purchases of real or financial

assets. Such transactions create two additional liabilities for banks, which

are regulatory: the capital requirement liability for the asset (loan or

investment), and the reserve requirement for the liability (deposit). And these

liabilities have to be met ex-post, not ex-ante as usually believed (see, for

example, "Reserve Computation and Maintenance Periods" section of the

"Reserve Maintenance Manual" of the Fed, for reserve requirement

liabilities)[2],

meaning banks are not constrained by capital or reserve requirements but mainly

by "profitability and solvency considerations (Jakab and Kumhof

2015)."

To meet the capital requirement, banks can

sell shares, raise equity-like debt or retain earnings, and Carney (2013) gives

detailed examples of how banks can do these. We refer the reader to his article

for this. However, the Central Bank is the monopoly creator of the reserves,

meaning banks have to meet the reserve requirement by obtaining the reserves

from the Central Bank. There currently are a few countries, such as the UK and

Canada to name two, where there is no reserve requirement but banks need

reserves to settle accounts with other banks whether there is reserve

requirement in the country or not.

Under the current institutional arrangements,

the Central Bank can create reserves through:

1) the loans it makes from its so-called discount

window and, if exist, certain liquidity facilities to the banks and qualified

others;

2) the reverse repurchase agreement

transactions (so-called open market operations) with its counterparties to buy

Treasury and other securities it deems fit;

3) the purchases of Treasury securities (so-called

quantitative easing) and other financial securities it deems fit (so-called credit easing) in the secondary

market,

as these transactions

create new deposits in the accounts of banks at the Central Bank. If, on the

other hand, the Central Bank signs a repurchase rather than a reverse

repurchase agreement through open market operations, it creates reverse

repurchase liabilities, depleting some reserves. The reason is that in a repurchase agreement

one party pledges collateral to a counterparty to borrow funds with the promise to purchase the collateral

back at an agreed price on an agreed future date, and while the agreement is a

repurchase agreement from the point of the borrower, it is a reverse repurchase

agreement from the point of the lender. Hence, the transformation of some reserves

to reverse repurchase liabilities.

This is where the Treasury

comes in. The Treasury provides most of the collaterals acceptable to the

Central Bank through which the Central Bank creates most of the reserves.

Further, the Treasury maintains the account from which it makes its payments at

the Central Bank in all countries, although it may maintain accounts at some

designated commercial banks also (see Yaker and Pattanayak 2010). We should

mention that, leaving aside the questions of why and since when, the Central

Bank can currently lend to the Treasury or purchase securities from the

Treasury hardly in any country. The "central bank independence"

reigns supreme by law, although not necessarily in practice.

Other than banks and the

Treasury, there usually are a few other entities that are allowed to maintain deposit

accounts at the Central Bank in every country, not to mention foreign central

banks. All deposits other than bank deposits at the Central Bank, including

reverse repurchase liabilities, drain reserves if they go up. In other words, all

deposits other than bank deposits at the Central Bank should be viewed as a fourth

type of money, since changes in their balances impact reserves, that is, base

money, so that they should be managed in order not to create liquidity problems

in the domestic banking system (see, for example, Pozsar 2019).

We conclude this section

with the following observations.

1) When the Treasury sells

its bonds to the non-bank rest, there is no new money creation. Only existing

money changes hands, and if that money gets deposited in the TSA, equal amounts

of reserves and deposits get extinguished. Likewise when tax payments get

deposited in the TSA. But after the

Treasury spends the deposited amount, both base money and broad money come back to where they were

before, keeping everything else constant.

2) When the Treasury sells

its bonds to banks, three things may happen.

a) If there are banks at

which the Treasury can maintain deposit account with or without restrictions,

or there are no such banks and only those banks at which the Treasury cannot

maintain deposits accounts purchase the Treasury bonds, then these banks buy

the Treasury bonds by borrowing from the Central Bank against which the Central

Bank increases the balance of the TSA. After the Treasury spends the balance,

an equal amount of base and broad money get created.

b) If there are banks at which the Treasury

can maintain deposit accounts without restrictions and only those banks at

which the Treasury can maintain deposit accounts without restrictions purchase

the Treasury bonds, then new broad money gets created as usual. But since the

Treasury has to spend only from the TSA, the result is the same as above.

c) If there are banks at

which the Treasury can maintain deposit accounts with restrictions, then a

combination of the above two happens.

These observations mean

that whether the Treasury sells some amount of the bonds to banks or the same

amount directly to the Central Bank (or the Central Bank loans the same amount

to the Treasury), the changes in the base and broad money are the same after

the Treasury spends the amount, keeping everything else constant. The latter

is, of course, cheaper for the Treasury because the Central Bank has to pay a large

percentage of its profits to the Treasury in every country, whereas the banks, generally, do not.

Sonradan ek: Bitti.

Modern Money

Creation

"It

is much more realistic to say that the banks 'create credit,' that is, that

they create deposits in their act of lending, than to say that they lend the

deposits that have been entrusted to them. And the reason for insisting on this

is that depositors should not be invested with the insignia of a role which

they do not play. The theory to which economists clung so tenaciously makes

them out to be savers when they neither save nor intend to do so; it attributes

to them an influence on the 'supply of credit' which they do not have. The theory of 'credit creation' not only recognizes

patent facts without obscuring them by artificial constructions; it also brings

out the peculiar mechanism of saving and investment ... Nevertheless, it proved

extraordinarily difficult for economists to recognize that bank loans and bank

investments do create deposits." − Joseph Alois Schumpeter (1954)

The above is from Schumpeter's History of Economic Analysis, published

in 1954. Let us now look at two earlier works: Henry Dunning Macleod's The Theory and Practice of Banking, published in 1855-6 in two

volumes, and Robert Harrison Howe's The

Evolution of Banking: A Study of the

Development of the Credit System, published in 1915. Both scholars go at

lengths to describe how modern banks create deposits by extending credit or

buying real and financial assets. Building on Macleod (1866 [1855-6]), one of

the most influential early proponents of the Credit Creation Theory (CCT) of banking, Howe (1915) defines modern banks as follows.

"Our

modern banks are Banks of Discount as distinguished from their predecessors,

the Banks of Deposit, and have given an enormous impetus to commerce. They have

been able to do this because they can and do create credit that circulates the

same as money and in a far more convenient, safe and economical form."

Ravn (2019) clarifies as follows.

"In

a nutshell, other financial, non-bank firms can lend alright, but they pay out.

Banks don’t. Credit that is entered into a firm’s Accounts Payable during

lending is, in a bank, never discharged, but is renamed Customer Deposits and

serve as the money supply, by virtue of this credit being transferable and

accepted in payment by other banks and their customers."

Although not accepted as a universal truth,

the CCT had remained the dominant theory of banking until the early 1930s when

the Fractional Reserve Theory (FRT), one of the early proponents of which was

Alfred Marshal (1888), had replaced the CCT as the dominant theory.

The FRT can be summarized as follows.

Some seed money comes to the banks, and the

banks multiply that seed money. The banks do this multiplication by keeping a

percentage of that money as reserves and

extending the rest as loans to the public, which ends up as deposits at some

other banks. The banks then keep doing this among themselves until there is no

money left to lend and, in the process, create additional deposits—that is,

additional money—whose sum is equal to the sum of the loans extended. For

example, if the reserve ratio the banks abide by is 10%, the banks multiply the

seed money by 10.

Therefore, the FRT can also be called the

Deposit Multiplication Theory (DMT) in which although each bank is a financial

intermediary, the banking system creates money collectively as described above.

Whether the DMT or the FRT, the theory had remained in the back burner until

the end of World War I, when it started to gain prominence. One of the most

influential proponents of the FRT was Phillips (1920), and there had been many

others. By the early 1930s, it became the dominant theory and had remained so

until the 1960s.

The theory that replaced the FRT as the

dominant theory is the Financial Intermediation Theory (FIT) of banking, one of

the early proponents of which was von Mises (1912). The FIT challenge to the

FRT started with the seminal paper of Gurley and Shaw (1955) in which they

argued against the view that “banks stand apart in their ability to create

loanable funds out of hand while other intermediaries in contrast are busy with

the modest brokerage function of transmitting loanable funds that are somehow

generated elsewhere.” Later, Gurley and Shaw (1960) argued that the

similarities between the monetary system and non-monetary intermediaries are

more important than the differences, and that, like other financial

intermediaries, banks and the banking system have to collect deposits and then

lend them out. Then came the support of Tobin (1963) after which the FIT became

the dominant theory and had remained so, at least, until the start of the GFC

in the summer of 2007.

While Werner (2014, 2016), and Jakab and

Kumhof (2015, 2019) give detailed historical accounts of the evolution of the

three banking theories, Werner (2014, 2016) also provides empirical tests

rejecting the FRT and FIT and showing that the CCT alone conforms to empirical

facts. An earlier empirical work rejecting the FRT is a Fed working paper in

which Carpenter and Demiralp (2010) demonstrate that the relationships implied

by the FRT do not exist in the data.

More recently, Ravn (2019) examined the three theories, and although he

did not dispute the validity of the CCT for the current banking and monetary

system, concluded that the FRT and FIT do not need to be condemned to the dust bin

of history because the money incarnations of each banking theory facilitate

their appropriate use in analysis of historical and future banking and monetary

systems and argued that although under current conditions individual banks can

and do indeed create money all on their own, one should not downplay the

enabling role that clearing plays in facilitating money creation, absorbing the

money created and concealing the origin of money in banks' credit creation.

A fourth theory which had remained at the

fringes until recently is the State Theory of Money—also known as chartalism (the

Latin word "charta" means ticket, token or paper)—formulated by George

F. Knapp (1973 [1905]). According to Knapp who coined the name chartalism, money

is "a creature of the state", and Rochon and Vernengo (2003) argue

that Knapp seems to suggest that this is because the State determines the unit

of account. Indeed, citing Knapp, Keynes (1930) also asserts that "the age

of chartalist or State money was reached when the State claimed the right to

declare what thing should answer as money to the current money of account—when

it claimed the right to enforce the dictionary but also to write the

dictionary", and that "[t]oday all civilized money is, beyond the

possibility of dispute, chartalist." Later, Abba Lerner (1947) brought to

the fore taxation as the main cause for the acceptability of money because

"before the tax collectors were strong enough to earn for the State the

title of creator of money, the best the State could do was tie its currency to

gold or silver," although neither Knapp nor Keynes made such a claim.

The Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) —also known

as neo-chartalism—recently popularized by the American politicians Bernard

Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio Cortez is a form of chartalism. Wray (2014)

describes the role chartalism plays in the MMT, and Lavoie (2014) provides a

friendly critique of neo-chartalism (also see Rochon and Vernengo 2003). According

to the MMT, money is injected into the system by the government as the monopoly

issuer of currency, and the banking sector leverages the government-injected

money, increasing the amount of money in circulation. While the MMT argues that

what is necessary for the existence of a monetary economy is the State power to

create money and to ensure its general acceptance by imposing taxes, many of

its critics object to the MMT emphasis on taxes and argue that what is

essential for the existence of a monetary economy is the State's ability to

enforce the civil law of contracts under which contracts are settled.

Although the origins of the MMT go back to

the early 1990s and debates on neo-chartalism have been going on for longer

than a decade, since many new supporters and opponents have jumped in the wagon

after the MMT became popular in the summer of 2018, the intensity of the

debates has been growing. The reader can consult, for example, the October 1,

2019 issue of the Real-world Economic Review for a recent debate.[1]

A detailed discussion of the MMT is

beyond the scope of this article. However, focusing only on the payment and

settlement aspects of the MMT, we mention that an important contribution of the

MMT is the clarification of the role the Treasury account at the Central Bank—the

Treasury General Account (TGA) in the US and the Treasury Single Account (TSA)

in most other countries (see, for example, Yaker and Pattanayak 2010)—plays in

the money creation process.

In the rest of this section, we give a brief

description of domestic money creation, which we will need in the next section.

In many jurisdictions, domestic banks can create foreign currency (mainly US

dollar and euro) deposits by extending foreign currency loans also, but we

leave this out for simplicity. Further, we avoid discussing the roles the

international monetary system, as well as shadow banks, play in modern money

creation also for the same reason.

Since we ignore the shadow banks and the rest

of the world for simplicity, there remain four major players in domestic money

creation: (1) the Treasury, (2) the Central Bank, (3) the banks, and (4) the non-bank

rest consisting of non-bank financial corporations, non-financial corporations,

and households. A fifth player is the banking regulator unless the Central Bank

is it, and there are many jurisdictions in which there are multiple banking

regulators. Irrespective of the case, however, it is always the Central Bank

that sets the reserve requirement as the reserve requirement is a monetary

policy tool, whereas the banking regulator sets the capital requirement (see,

for example, Öncü 2017 for a detailed discussion), among other things.

The three primary types of money in current domestic

monetary systems are (1) cash (banknotes and coins), (2) reserves (deposits of

the banks at the Central Bank), and (3) customer (non-bank rest) deposits at

the banks or, for short, deposits. Deposits are claims on the Treasury created

cash, as well as on the Central Bank created reserves. As empirically demonstrated by Werner (2014,

2016), only the CCT conforms to empirical facts, meaning banks create deposits

by extending loans and purchasing real or financial assets. Or, in Schumpeter's

words, "bank loans and bank investments do create deposits (Schumpeter

1954)."

However, as Carney (2013) pointed out, bank

"loans create a lot more than deposits," and we add that the same is

true also for bank investments, that is, bank purchases of real or financial

assets. Such transactions create two additional liabilities for banks, which

are regulatory: the capital requirement liability for the asset (loan or

investment), and the reserve requirement for the liability (deposit). And these

liabilities have to be met ex-post, not ex-ante as usually believed (see, for

example, "Reserve Computation and Maintenance Periods" section of the

"Reserve Maintenance Manual" of the Fed, for reserve requirement

liabilities)[2],

meaning banks are not constrained by capital or reserve requirements but mainly

by "profitability and solvency considerations (Jakab and Kumhof

2015)."

To meet the capital requirement, banks can

sell shares, raise equity-like debt or retain earnings, and Carney (2013) gives

detailed examples of how banks can do these. We refer the reader to his article

for this. However, the Central Bank is the monopoly creator of the reserves,

meaning banks have to meet the reserve requirement by obtaining the reserves

from the Central Bank. There currently are a few countries, such as the UK and

Canada to name two, where there is no reserve requirement but banks need

reserves to settle accounts with other banks whether there is reserve

requirement in the country or not.

Under the current institutional arrangements,

the Central Bank can create reserves through:

1) the loans it makes from its so-called discount

window and, if exist, certain liquidity facilities to the banks and qualified

others;

2) the reverse repurchase agreement

transactions (so-called open market operations) with its counterparties to buy

Treasury and other securities it deems fit;

3) the purchases of Treasury securities (so-called

quantitative easing) and other financial securities it deems fit (so-called credit easing) in the secondary

market,

as these transactions

create new deposits in the accounts of banks at the Central Bank. If, on the

other hand, the Central Bank signs a repurchase rather than a reverse

repurchase agreement through open market operations, it creates reverse

repurchase liabilities, depleting some reserves. The reason is that in a repurchase agreement

one party pledges collateral to a counterparty to borrow funds with the promise to purchase the collateral

back at an agreed price on an agreed future date, and while the agreement is a

repurchase agreement from the point of the borrower, it is a reverse repurchase

agreement from the point of the lender. Hence, the transformation of some reserves

to reverse repurchase liabilities.

This is where the Treasury

comes in. The Treasury provides most of the collaterals acceptable to the

Central Bank through which the Central Bank creates most of the reserves.

Further, the Treasury maintains the account from which it makes its payments at

the Central Bank in all countries, although it may maintain accounts at some

designated commercial banks also (see Yaker and Pattanayak 2010). We should

mention that, leaving aside the questions of why and since when, the Central

Bank can currently lend to the Treasury or purchase securities from the

Treasury hardly in any country. The "central bank independence"

reigns supreme by law, although not necessarily in practice.

Other than banks and the

Treasury, there usually are a few other entities that are allowed to maintain deposit

accounts at the Central Bank in every country, not to mention foreign central

banks. All deposits other than bank deposits at the Central Bank, including

reverse repurchase liabilities, drain reserves if they go up. In other words, all

deposits other than bank deposits at the Central Bank should be viewed as a fourth

type of money, since changes in their balances impact reserves, that is, base

money, so that they should be managed in order not to create liquidity problems

in the domestic banking system (see, for example, Pozsar 2019).

We conclude this section

with the following observations.

1) When the Treasury sells

its bonds to the non-bank rest, there is no new money creation. Only existing

money changes hands, and if that money gets deposited in the TSA, equal amounts

of reserves and deposits get extinguished. Likewise when tax payments get

deposited in the TSA. But after the

Treasury spends the deposited amount, both base money and broad money come back to where they were

before, keeping everything else constant.

2) When the Treasury sells

its bonds to banks, three things may happen.

a) If there are banks at

which the Treasury can maintain deposit account with or without restrictions,

or there are no such banks and only those banks at which the Treasury cannot

maintain deposits accounts purchase the Treasury bonds, then these banks buy

the Treasury bonds by borrowing from the Central Bank against which the Central

Bank increases the balance of the TSA. After the Treasury spends the balance,

an equal amount of base and broad money get created.

b) If there are banks at which the Treasury

can maintain deposit accounts without restrictions and only those banks at

which the Treasury can maintain deposit accounts without restrictions purchase

the Treasury bonds, then new broad money gets created as usual. But since the

Treasury has to spend only from the TSA, the result is the same as above.

c) If there are banks at

which the Treasury can maintain deposit accounts with restrictions, then a

combination of the above two happens.

These observations mean

that whether the Treasury sells some amount of the bonds to banks or the same

amount directly to the Central Bank (or the Central Bank loans the same amount

to the Treasury), the changes in the base and broad money are the same after

the Treasury spends the amount, keeping everything else constant. The latter

is, of course, cheaper for the Treasury because the Central Bank has to pay a large

percentage of its profits to the Treasury in every country, whereas the banks, generally, do not.

TÜSİAD'ın yeni vergi düzenlemesine itirazı

TÜSİAD'ın itirazı

Normal. 1952'deki Alman Lastenausgleich (yüklerin dengelenmesi) yasasının başına da aynı şey geldiydi. Sonunda tabii sermaye tarafı kazanınca yasa kuşa döndürüldü ve yükün ağır kısmı Alman işçi sınıfı, köylüler ve küçük esnafa yıkıldı. Hep öyle oluyor son 3500-3600 yıldır.

Sunday, November 10, 2019

Nasrullah Ayan'dan önemli bir video daha.

Nasrullah Ayan'dan önemli bir video

Nasrullah hala paranın nasıl yaratıldığını anlamıyor, bankalar verecekleri krediler için parayı nereden bulacaklar dediğinden ama orası önemli değil.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)